The line stretches from the Student Union to the PAB entrance. For the last two hours, students—mostly without masks, breathing on each other’s’ necks—have lined up to get tested for COVID-19 so they can enter the university building and run to their classes.

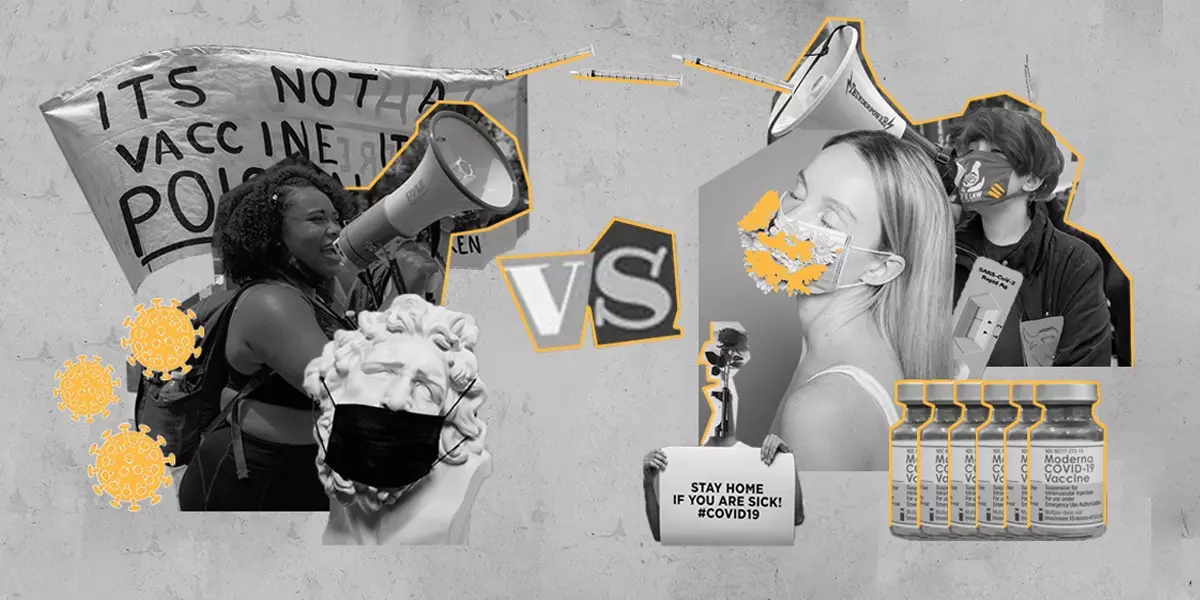

When everyone got the email announcing AUA’s new policy, students separated into two opposing fronts: those supporting the policy and those against it. “At first, I took it with a grain of salt,” shares Armen Torossian, Student Council representative and an EC junior. He explains that not all students work, make money but all of them have to come to the university and most have to pay for the tests. At the same time, he adds that the policy seems reasonable when looking at other issues at stake, such as health—the ultimate concern of the university administration.

Right after the pivotal email, students initiated a heated debate on the AUA Undergraduate Students Facebook group. Many created petitions in support of online learning, and others were asking for discounted prices for the PCR test. The university considered the latter and offered a much cheaper PCR test on the first Monday and Tuesday after the break, promising this is the only time the Health Clinic will organize it. Nevertheless, two weeks later, when the 14-day-period was over, and new test results were required, the university administration organized another affordable test drive.

Students are not against the policy, per se, but they are more concerned with the effectiveness of the regulations. “Even though AUA has “strict” rules regarding COVID, not everyone is obeying those properly,” claims Anna Ataberkyan, a Business senior. “Operating cafeteria is an example of how regulations do not apply at all.”

There are also other circumstances where the health measures are not enforced well enough. Torossian shares his distress with the classroom sizes in the Main Building; in the case of keeping social distance, they don’t fit thirty people. Another common concern is security surveillance. “No matter what they do with security, some students are still very stubborn,” says Torossian. Every day students find numerous excuses and ways to trick the security guards into not scanning their ID cards when entering the building. Thus, the more responsible students are worried that non-vaccinated or positive tested students might easily enter the building.

Even if, in the ideal world, students follow the rules, the regulation itself might be flawed. Students queuing for the first PCR test didn’t have to wait for one to three days to receive their test results. Those who passed the test received a green piece of paper indicating that they made an effort to follow the regulations. However, the results of their test remained unknown for a few days. They could easily be infected and enter the university without proof of their positive results. This became a concern for those students who do their best to follow the new policy. Taking into account this, the next testing was organized with rapid tests, that showed the results in 15 minutes. Yet, again, many were wondering how effective and reliable those rapid tests were.

On the opposing front, there are the pro-vaccine students and simply those who didn’t have any other choice but to get vaccinated; in other words, as they claim, they were pressured into getting vaccinated. With the vaccine supporters, it is sweet and easy. “Why not get vaccinated when the vaccines are safe and available in this country?” wonders Vana Bakalian, an EC sophomore. She believes that unlike the other countries, in Armenia, it is much quicker, and people choose which vaccine they want. “We should appreciate the efforts of the university,” points out Bakalian when talking about the vaccination drives the AUA organizes almost weekly.

The views again differ when it comes to those who got vaccinated because of institutional and societal pressure. Some reject the mere idea of it and don’t want to give in to the system, yet others support the controversial enforcement mechanism. “I think it is perfectly normal to make people get vaccinated by putting pressure on their pockets, and I wholeheartedly support it,” argues Harout Mirzakhanyan, a CS sophomore. “Vaccines are safe and effective. If someone does not believe this, then it is their problem,” adds Mirzakhanyan.

When given the option of online education, the pro-vaccine front does not want to hear about it. Many students moved to Yerevan and got vaccinated to attend the university in person and benefit from the AUA campus. With a switch to online learning, all their efforts would be in vain. Yet, the opposing front is filled with hypocrites that, last year this time, were claiming they were fed up with the distant learning and wanted to go back offline, and now are advocating for online education again.

In the last months, no one has reached the student council with their concerns and concrete suggestions. “We like to point out issues but never offer any solutions to it,” believes Torossian. “It’s easy to do that.”

Covid wars seem never-ending. The two opposing fronts of the student body do not want to give up their positions yet do not offer any tangible solutions either. As a result, AUA has an administration that claims to be doing its best, and students, generally unhappy with how things are going. At least, the beginning of the spring semester might bring new policies and regulations for the students to be unsatisfied with.