Diasporic communities, often formed based on shared narratives of traumatic historical experiences, are engaged in a paradoxical relationship with change: their past determines the present, but their future largely depends on how the new generations engage with both. As a result of the 1915 Armenian Genocide, hundreds of thousands of people found refuge in various parts of the world, forming what is known today as the Armenian Diaspora.

Collective memories and historical narratives underlie diasporic notions of loss or the regaining of homeland, return, and belonging. Diasporas become seen as connected through shared imagination and collective memory, which is sustained through the revival of shared historical experience in imagining their homeland.

Nirva Kuyumcu, EC junior, shared her experiences as a diasporan Armenian returning to her motherland.

Nirva was born and raised in Istanbul, Turkey. Her family is originally from Western Armenia; her paternal side is from Amasia, and her maternal side is from Atiaman. Both of her parents moved to Istanbul at a young age.

Although Nirva is from an Armenian family, she learned about Armenia mainly from her school teachers. In 2017, her piano teacher introduced her to the “Ari Tun” (“Step Toward Home”) program and she decided to visit Armenia. “It was my first visit and prior to that I did not know much about Armenia,” noted Nirva.

Being a member of the Armenian community in Istanbul and being exposed to both Armenian and Turkish cultures, as Nirva admitted, she did not get to fully understand and experience Armenian culture. “I had this idealized image of Armenia being the home to all its cultural aspects like language, cuisine, etc. that I did not get to experience properly in Istanbul,” added Nirva.

Nirva moved to Armenia in 2019 to pursue her studies at AUA. As she started getting more of an inside look at the country through a new lens, she got to experience a cultural shock to many different degrees.

Something that surprised her was seeing Armenia influenced by so many different cultures. “I did not know Russia had so much influence on Armenia on many different levels. That was a great shock for me,” Nirva admitted.

Ani Zadikian, ES senior, detailed her perspective on how her life has changed ever since she has been back to Armenia.

Ani was born and raised in Brazil. Her family history is divided into two parts. Her maternal great-grandfather, who was from Marash, Western Armenia, moved to Brazil during the Armenian genocide. Her paternal great-grandparents, who were also from Western Armenia, moved to Greece and then to Lebanon during the genocide.

During the Soviet period, Armenia started to call the diasporan Armenians back to their homeland. Both of her paternal grandparents moved back to Armenia and lived there for four years. They moved to Brazil from Soviet Armenia when Ani’s father was already 11 years old. “The government allowed people to move out of Armenia back then if there was someone who invited them from abroad,” explained Ani.

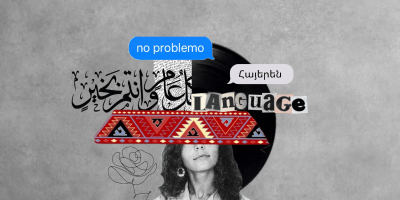

Nearly all of the Armenian communities in Brazil were formed due to the genocide and because they are so old, the Armenian language and most part of the Armenian culture is forgotten in those communities. However, Ani’s paternal grandmother had a strong influence on her in the process of introducing her to Armenian culture and language.

“Whenever I wanted to say to my grandmother something in Brazilian she would always make me switch to Armenian,” laughed Ani. She admitted that she did not know that her grandmother’s pressure to learn Armenian would be so rewarding for her in the future.

Like Nirva, prior to coming to Armenia, she had an image of Armenia as an ideal place that preserved all its national and cultural heritage—a place where she would finally feel completely at home. She moved to Armenia in 2018 right before the Armenian Velvet Revolution.

It is currently Ani’s fifth year living in Armenia and one of the things she appreciates here is the safety that she did not feel in Brazil. “It’s so liberating to be able to be outside at late hours without thinking that something bad will happen to you. It was not the same in Brazil. You would not guess something might happen if you were outside at a late hour. You were sure that something bad would happen.”

Both Ani and Nirva admitted that they don’t feel fully at home in any of the countries they live in. “I am too Armenian in Brazil, and I am too Brazilian in Armenia,” Ani remarked. Nirva never considers herself a “hayastantsi” (an Armenian from Armenia). “My nationality is Armenian, but I would also call myself an anatolitsi/polsetsi,” Nirva noted.

Although Nirva and Ani come from different backgrounds, their commonality is their “collective memory” that always reminds them who they are and where they come from. They both see that Armenia needs to go through changes on many different levels and they believe that they are also a part of the changemakers.