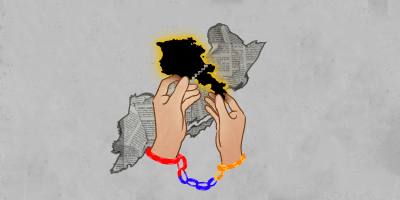

I always wonder what it’s like for diasporan Armenians who return to their homeland. I’m not Armenian, so I can’t say – though, inside, I always cry tears of joy when I hear about a diasporan returning for the first time and calling this place home. But, perhaps you could say that I’m a diasporan Filipino. As William Safran writes, the diaspora “have retained a memory of, a cultural connection with, and a general orientation toward their homelands… they relate in some (symbolic or practical) way to their homeland.” In my experience, I’ve lived outside of my country for more than half of my life, though I still preserve my Filipino identity in certain ways and often recall memories of my childhood in the Philippines.

To be honest, it’s been a struggle coming to terms with that identity ever since I became acquainted with the globetrotter’s life. I moved to Nepal with my family when I was 10, and in 2017, we moved to Armenia. I call both of them my second home. We’d still return to the Philippines every year for a month or two. But as I grew older, I experienced reverse culture shock, as I was faced with changes that had taken place while I had gone, and not many people were interested in hearing my stories from abroad. I’d struggle with keeping up with new slang and pop culture inside jokes, leaving me feeling out of place with my friends. The feeling of being a foreigner in my own land made me somewhat bitter toward my country and my people.

Then, I met diasporan Armenian friends at AUA. I had a Syrian-Armenian friend who sat with me and talked about how he had to adjust to life here and missed his home back in Syria, just like I missed the Philippines and had to readjust to life there whenever I went back. I realized that I wasn’t alone. The more I met diasporans, I saw how we had similar experiences with feeling out of place because of the language and cultural barriers of people who are supposed to be our own, but sometimes don’t accept us the way we want them to, and with being in environments that we aren’t used to because they’re different from what we call “home.”

Last summer, I finally went back to the Philippines after four years. My family went on our yearly trip to Manila in 2019 but left me here in Yerevan because I started studying at AUA. The COVID-19 pandemic also prevented us from going home until this year. Though, I didn’t know what to expect when we got back there.

Before our flight to the Philippines, a huge part of me didn’t want to leave Yerevan because I wanted to roam around in the summer without the restrictions of masks from the past two years of the pandemic. Perhaps it has also become my comfort zone. But the more important thing – which I didn’t want to admit – was that I was scared of going home, scared of being hurt again. I didn’t want to feel out of place in that one place where I should truly belong, even if I knew I had found second homes in Nepal and Armenia. I didn’t want to be ignored by my people.

So, when we entered Filipino airspace (after a two-hour flight to Qatar, a grueling 19 hours of layover in the Doha airport, and a nine-hour flight to the Philippines), I tried to convince myself that the land belonged to me by repeating to myself, “This land is yours. This land is yours.” because I didn’t fully believe it.

I wrote in my phone journal:

They’ve just released the legs of the plane or fixed the flaps. The windows outside are showing the yellow-dusty sky. I see fields, plains of green and brown. My first sighting of home – of my homeland, in four years. That’s mine. That land is mine.

“Be proud

To wear the colors that you call your own

Be loud

Speak out when you want the world to know…”

And I cried watching this scene from “Inkheart” on the airplane TV. There’s a character played by Paul Bettany (Vision in the Avengers films), who was a book character magically called into our world, and he was separated from his home for nine years. He was desperately looking for a way back all that time. At the movie’s end, when he wakes up and finds that he was finally returned to his book-land country, the narrator says, “It was just as beautiful as he remembered it.”

I cried because I wanted to see that for myself in the Philippines, even if I expected that I wouldn’t. In a way, I was wrong.

A Filipino sunset streaked with gold and pink greeted us outside the Clark International Airport, though later it rained, making the weather more humid. At the Arrivals, I first saw my teenage cousin John William with his bird’s nest of hair. His voice had changed since I last saw him, and I wanted to cry when I embraced him, but there were so many people waiting around us and I knew I had to keep moving so we wouldn’t get scolded by the guards and attendants.

We had lost his mom to cancer when I was in Armenia in 2020 (I cannot empathize with my Armenian friends who lost a friend or relative in the war, but I can relate to them in this way). When we ate dinner with them and were laughing and talking, I felt that something was missing or incomplete, as if I was walking off-balance or had lost an arm– and I remembered we didn’t have our aunt with us anymore.

After dinner, we continued the two-hour drive to Manila. We passed by malls I used go to frequently in my childhood and highways where we used to get stuck in traffic for hours. We cheered when we saw the headquarters of a news station whose broadcast we’d watch almost every night in Armenia. Finally, we reached my other uncle’s apartment (he’s been living and working in Indonesia, even before the pandemic), where we were supposed to stay, and it was just as I had remembered it since I last saw it in 2018. He still hadn’t replaced one of the ceramic cacti in the bedroom, which one of my cousins broke (no one has confessed). So, I was so happy to be home that I didn’t have space to feel out of place.

Of course, the main thing about being back was being able to eat the food that I could only get in the Philippines! Seafood, seafood, seafood. The diversity of seafood we had there was much more diverse. We wolfed down our favorite kinds of fish, squid, and shellfish – my favorite version is served with cheese – shrimp, crab, sushi, sashimi, and so on. I could eat all the Filipino snacks I wanted, which we’d ask people going to Armenia to bring for us. I got to taste an iced mango shake again after four years.

I was also so grateful to have a certain endemic Filipino ingredient in my favorite dish, sinigang, which is a sour soup meal with meat and vegetables – tomato, onion, kangkong leaves, and sometimes with eggplant (in Armenia, we substitute the leaves with lettuce and the eggplant sometimes with zucchini, and we use sinigang sour powder mix imported from Filipino stores in the Middle East). The ingredient was a potato-like vegetable named gabi, which my mom put in the soup for us. That moment I tasted it again made me feel that I was truly home.

Another thing that is connected to the Filipino experience is the malls. We have hundreds of them in Metro Manila – after all, we have a population of 10 million there. Malls in the Philippines are massive. They usually have five floors, most ranging from three to ten times the floor area of Yerevan Mall. If parks are where most people in Yerevan hang out, it’s the malls in the Philippines. Everyone goes there because there’s air conditioning, many restaurants and food chains (with cuisines including Italian, Arabic, Japanese, Korean, and Chinese), big groceries, department stores, and shops for anything and everything (my favorites were the secondhand book sale, comics store and Filipino stationery shops).

The next week, we went to one of the malls and I had to find a bathroom before we left. Not wanting to drop by a random restaurant, I went to the basement floor, where I passed the arcades and remembered where the old bathroom was – after four years. I prided myself on that.

I remembered how I once talked to a professor about how places change over time and nothing about them is ever truly permanent – yet I was there remembering directions to old places after four years. The concept of impermanence, which my professor shared with me, helped me cope with the changes I saw in the Philippines.

In our class during the past semester, he introduced this idea of impermanence in architecture – where nothing is truly permanent with structures because they decay due to the elements, and new meanings are assigned to them by new generations that come and use them for things differently intended by their architects and initial users.

I wrote to him about how this concept of knowing places could never stay the same helped me accept those changes (he, of all people, would also understand what change is because he was born and raised in Lebanon as a child but left during the civil war). That sense of closure helped me appreciate the old memories of those places without holding on to them too much. Then I would be able to celebrate the new memories I would be making in my homeland.

The Korean invasion was a new development in the country that we found interesting. Korean groceries, hair salons and restaurants were everywhere. K-Pop stars and K-drama actors would be on giant billboards and promoting different businesses on the same level as Filipino celebrities. It was to my sister’s joy – three days after we landed in the Philippines – to attend a K-Pop concert with NCT Dream (sans Mark and Haechan) and SHINEE’s lead vocalist, KEY. I chaperoned her and her best friend, whom she hadn’t seen for three years.

When I met my family and friends again, it was interesting to see how much they’d grown. However, social media helped it seem that I had never left because we were often connected to them – my cousins would attend our Zoom birthdays or hang out with each other on Discord. And now, we had something more in common: we went through COVID with the same fears and online ordeal and similar losses.

I didn’t feel as foreign to them this time going home because of that. I told them about the unique pain of living through a war where I lost seven university mates in 2020, one in the same class as me. They wouldn’t be able to understand that, but I’m glad that they listened.

I also got invited to speak at my old homeschool school as an alumna, and I felt a little shy because they were so proud of me for being a TEDx speaker (thanks to AUA!) I also met three former homeschoolers who had come back to the Philippines for the summer from their universities in the US.

Another ease of being in my homeland was speaking the language. Although I couldn’t joke as well as others (humor is my handicap), I could express myself so much more. It was really helpful to speak without obstruction to taxi drivers, security guards, and staff in the malls or in restaurants. (I missed saying “barev dzez” to people in shops because we don’t really greet each other there.)

And it was amazing to go back to church there and sing my heart out to God in Tagalog with my fellow Filipinos leading the worship and the audience singing along around me. I’d often have to change my mask because it would be soaked with tears after the songs. It had been four years since I was able to sing with this family.

We also returned to my parents’ island hometown, Masbate, for a very short time of six days. My parents used to bring my sister and me there every Christmas until we moved to Nepal (my brother Jivan was born after our first year there). It’s one of the places in the world that I hold most dearly in my heart. I loved going to the beach and my maternal grandparents’ home with my Lola (Grandma) Cory’s immense collection of books and walking on the streets so close to the sea.

After our plane landed, we took our bags where the porters spoke in our Masbteño dialect and greeted my parents, whom they knew. I saw my paternal grandma, Lola Lyd, at the door and she embraced us with tears running down her mask, which still obscured her face from us. I rode the tricycle driven by my uncle Neil, who I just called the term Kuya – ‘older brother’ – and made small talk.

I still couldn’t believe I was there, so I felt like a participant observer and looked at the streets from the motorbike seat the way our Cultural Geography professor taught us: “So, this is provincial life. There are small shops everywhere. The cement buildings are corroded with gray at their corners and edges. Schools have walls with murals on them. Now we’re passing by a sign that says ‘Welcome to Masbate City: Rodeo Capital of the Philippines’ with a cowboy statue – that’s how this province markets itself to the country, using the cowboy brand.”

Soon we went into a familiar street, but I wasn’t sure if it was our street, Bagong Camino. Then it hit me. I was really back.

The two tricycles drove into my grandparents’ garage, and I saw Lola Cory standing by her garden with a big smile. My quiet grandma was full of joy and embraced us under the trees she had been caring for.

That day, even if we hadn’t slept all night, we pored over our old photo albums while the adults talked. I saw my parents and uncles and aunts’ younger selves in faded brown photographs. My grandma had the same short haircut when she was a young teacher. I asked her what it was like for her as a grade school teacher there in Masbate. This interview was something I looked forward to about going back home because of one class under Maria Titizian, who told us to talk to our relatives and ask about their stories.

On the weekend, we went to the beach with our relatives – the only time we got to visit a beach in the 7,600 islands of the Philippines. We rode a boat out to the island of Buntod Beach, only, there was no island as it was high tide and the waters covered the white sands. It wasn’t high enough so that people were already swimming above the submerged sandbar. My family went up to the large hut of the island and ate together – the highlight for me was the fish and mussels. I drew the island, the skyline and the other moored boats surrounded by swimmers with my colored pencils while my grandmothers chilled out with the family.

Soon we went down to swim and collect seashells until the water finally subsided and we could walk on the white sands. We followed the strip of sand to the mangrove trees – the ocean’s nurseries – where our family took pictures together under the sun’s brightness. I swam to the roots of the mangrove trees, where I found zebrafish, clownfish, small crabs and other types of marine creatures.

My Dad followed me and spotted a school of fish leaping from the water in the distance. We were about to approach them quietly until he was distracted by a discovery of starfish in the sand. He gave one to me – it was sandy-gray, rough on the top and full of tiny little suction legs that helped it crawl on the ocean floor. We both remembered a picture he took of me as a child in a pink swimsuit, carrying red-brown starfishes and throwing them back in the ocean so they could live.

When I look back at my summer in the Philippines, I think, “Wow, that actually happened?” It’s like a different world. I’d never felt that before, maybe because I’m so used to AUA and Yerevan life now (my diasporan friends feel out of place – I’m not alone in that, they understand – an unspoken layer of understanding).

Yet, when I returned, I discovered that my knowledge about the Armenian diaspora– especially how my friends were eager to learn about their culture more – prepared me and changed my perspective about being back there – in other words, it made me less bitter. And besides, being away for four years made me miss my country so much that being on Filipino soil again made me really happy.