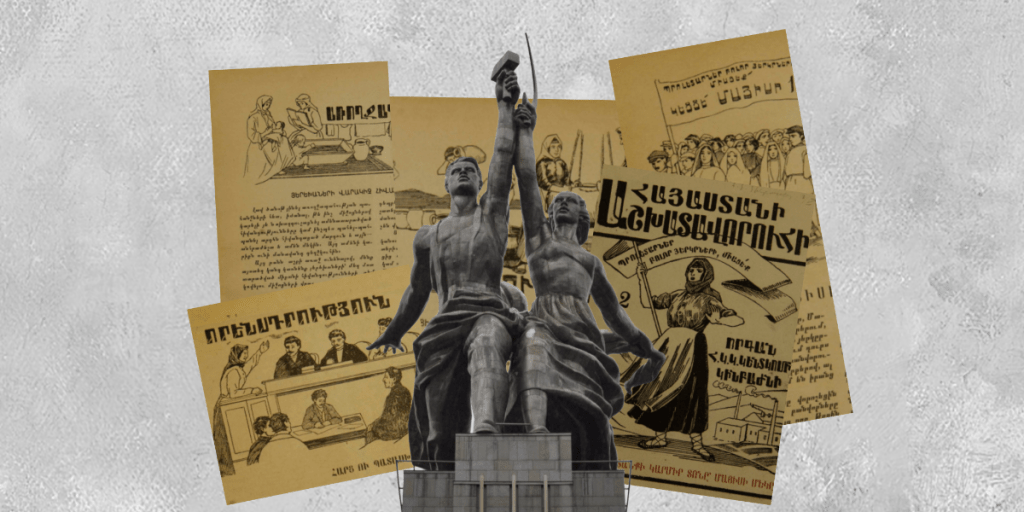

Did the Soviet Union truly emancipate women?

Throughout history, women around the world were subjected to discrimination by patriarchal societies, which was no different in Soviet Armenia.

The Soviet system pretended to free women by letting them work, but it actually used them as both workers and caregivers. This double burden of work and family life was often difficult to bear, yet a lot of women romanticized their lives in the Soviet Union up until now.

The Soviet Union’s political agenda of industrialization created the illusion of women’s emancipation. In the 1930s, the Communist Party organized social campaigns to encourage women to join the workforce, primarily for economic purposes rather than ideological shifts. As a result, women’s liberation did not really affect their lives at home. They remained responsible for household chores and childcare in addition to taking care of the financial aspects of their families.

The life story of Osanna Hakobyan, who lived during the early years of the Soviet Union, showcases the reality of post-Soviet societies concerning the female presence in the industrialized state.

She provided a glimpse into the family she was primarily socialized in, where the notion of a “working woman” was normalized for her not because Soviet legislation gave women the right to work but because the breadwinner (her father) had a disability, which justified the role of her mother as the breadwinner. Her primary gender socialization occurred through the roles her parents carried, which impacted her married life, as she was not just a housewife, unlike most of her peers in that village. “I started to work when I was 18, in 1975,” Hakobyan continued. “I was giving the whole money that I worked to my father-in-law.”

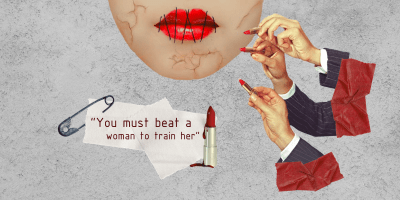

Despite the Soviet law giving women the right to work, the patriarchal system and society did not undergo cognitive liberation to accept those changes. Women’s emancipation was a fake agenda, and they were not liberated in their private lives.

Hence, by taking her financial independence, Hakobyan’s father-in-law tried to prevent the so-called woman’s over-emancipation because it would have threatened their privileges and rights as a wealthy family. As Hakobyan remarked, the word of her father-in-law was a law; the father-in-law was the decision-maker in traditional households. If they did not take financial independence from women’s hands, they could lose their authoritative role which would oppose the concept of a “strong socialist family.”

This concept further entailed having a stable marriage with high fertility rates because they made up the primary cell of socialism. Abortion was forbidden in 1936, and divorce was more difficult and expensive. Also, women were encouraged to have many children while still going to work.

This principle was manifested in Hakobyan’s father-in-law’s decisions related to her private life. Even though she already had two sons, her father-in-law did not allow her to have an abortion because it would have destroyed his “strong socialist family” fairytale.

While the Soviet government encouraged women to join the workforce, it did not really result in gender equality. Women were still expected to fulfill their roles as mothers, wives, and daughters-in-law. This often led to a double burden of work and family life. Hakobyan mentioned that she had to work hard during the week and dedicate the weekends to heavy housework.

Patriarchy was also covertly exercised in the public sector. High-paid jobs were mainly for men, and career development was almost impossible for women. Hakobyan confirmed this, “Starting from 1978, women were fully involved in the workplace. They didn’t have high positions … only a few women had high positions.” She also says that women were more responsible because they put much effort into having a job and getting promotions.

The collapse of the Soviet Union brought new problems for working-class families. The system that integrated women into the labor force on behalf of industrialization took them out of the workplace immediately after its collapse. As a result, the whole narrative and practices changed; the image of a strong socialist family stayed in the past because post-Soviet societies were no longer deprived of social problems.

Hakobyan mentioned that she was no longer eligible to work as an accountant as she used to, and it was hard to find work in general. Men took up high-position jobs, leaving women with low-ranking jobs. As she said, men unable to occupy high positions went abroad, leaving all the family-related burden on women’s shoulders. This meant that the whole social image shifted, and dysfunctional families became common.

In villages, the situation was different as cattle breeding and agriculture became optional jobs for men. Once Hakobyan started to work as an elevator operator, she achieved a new status in the family after the death of her father-in-law; she became the breadwinner and had the right to run the family’s finances.

Hakobyan’s story is a reminder that women’s lives in the Soviet Union were complex and often contradictory. While the government promoted women’s emancipation, they still faced discrimination in both public and private, which continues today even after the collapse of the system as the ideology is still alive in people’s mindsets.

Recent studies have shown that despite making up 61% of the educated population, women still only make up only 48% of the workforce as of 2021, working in positions that are mainly in administrative or care-taking roles rather than decision-making or leadership positions. There is also a 28.4% gender pay gap between men and women. These practices will not change unless societies undergo cognitive liberation.