July 12, 6 p.m. on the Kievian Bridge. The fiery sky blazes above the city, casting a warm glow over the Tumo park below. My friend, Karen, pulls out his phone to take a photo of the breathtaking sunset. Suddenly, an African woman nearby turns to us, her face reflecting a mix of frustration and sadness. For a moment, we’re confused—until we realize she thinks we’re photographing her, not the sunset. What was, for us, a peaceful moment admiring the sunset became, for her, a painful reminder of feeling excluded and alienated.

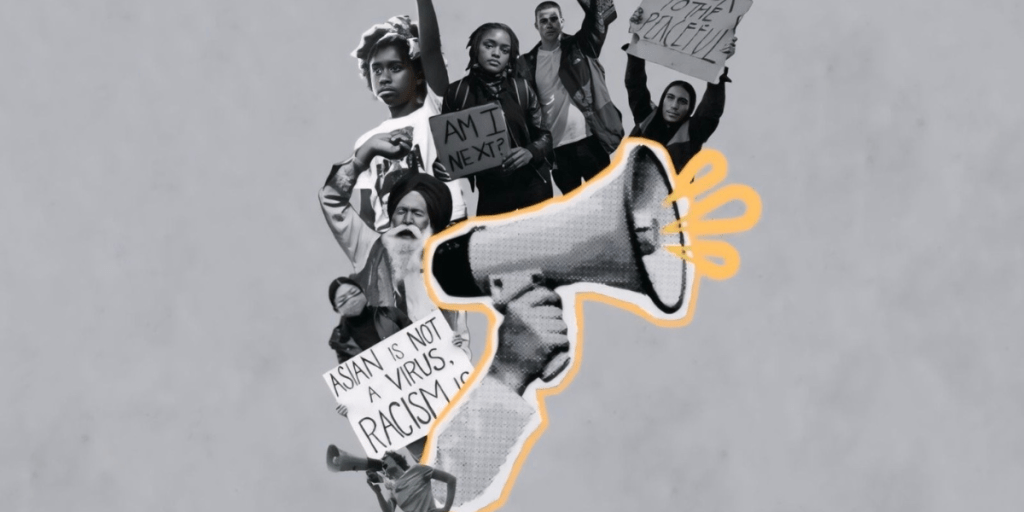

In a country where ethnic Armenians make up over 98 percent of the population, those who do not fit the norm often find themselves marginalized. Instances of racial bias range from outright discrimination to subtle microaggressions in both personal interactions and institutional practices. Discrimination can affect people of various descents, including ethnic Armenians with “non-European” features.

On a Facebook group for foreigners in Armenia, a light-hearted post by a man named Ivan (not his real name)—joking about how eggs in Armenia are harder to peel—quickly turned ugly. What started as a simple joke drew comments from a couple of Armenians, who told him to “go back where you come from” and called him “a brat” and “an asshole” for not learning basic skills. We see here how even trivial matters can trigger deeply ingrained racism and nationalism, making foreigners feel unwelcomed.

When Sergei Volkov, a refugee from Russia, first arrived in Yerevan, he felt the warmth of Armenian hospitality. However, it wasn’t long before he and his fiancé encountered subtle – and sometimes not so subtle – forms of discrimination. “People were curious at first and seemed friendly, but once they realized I wasn’t planning to leave soon, their attitudes changed,” he shared. “We started facing difficulties in renting an apartment, with landlords making excuses or suddenly raising the rent.” His fiancée, Chen Yue, faced her own challenges. During a Yandex ride, a driver casually remarked, “East Asians are not real humans.” The fiancée said, “The comment revealed not just an attempt to make me feel unwelcome, but also the disturbing ideas some people hold about other races.”

Many Indian students studying at Armenian universities report facing overt racism in public spaces, such as being refused service at certain establishments or hearing racial slurs. “I used to love going out with friends in Yerevan,” says Arjun Kumar, a med student at Yerevan State Medical University. “But after a few incidents where strangers yelled at us, calling us names, I started avoiding certain areas.”

But what drives this kind of behavior?

Armenia, being a small, largely homogeneous country with a complex history, has had limited exposure to diversity. During the Soviet era, Armenians had interactions with people from various republics, but these interactions were within the controlled environment of the USSR. Since independence, Armenia’s relative isolation and lack of cultural diversity have contributed to the persistence of stereotypes and xenophobia.

Another factor is the lack of comprehensive education about diversity, racism, and global cultures. Schools in Armenia often do not cover these topics in depth, leaving young people with limited understanding of different races and nationalities. This educational gap perpetuates ignorance, which can turn into fear or hostility toward those who are different.

However, it’s crucial to acknowledge that not every foreigner in Armenia has a negative experience. Andrea Shannon, who visited Armenia from the US, recalls an incident that left a positive impression: “Sometimes, locals try to cut in line when they see my foreign face. But Armenians often stand up for me, telling them to go back to their place in line, sometimes even causing arguments. This, to me, is worth more than anything. Many people in the US see racism or xenophobia and do nothing.”

Andrea’s story, along with others like it, reveals that compassion and a sense of justice do exist within Armenian society. One cannot ignore the fact that for Armenia to change, there has to be the acceptance of the presence of overtones and to work towards change, the prejudices have to go. Only then can the true beauty of the country—much like the sunset on the Kievian Bridge—be fully appreciated and shared by all, regardless of background or nationality.