It was a casual Saturday in September. While returning home from a store with the idea of enjoying the weekend, I cherished the peace of that September evening as the sunset was painting the sky with hues of purple and gold, creating an intense glow over the sky and taking solace in the soft embrace of twilight.

The next morning, I awoke to the pleasant warmth of an ordinary autumn day, with the possibility of a quiet Sunday stretching in front of me like an empty canvas ready to be filled with hopes and dreams. Approaching the kitchen window, where I usually kept my notebook and pen, I looked out, catching the warm rises of the sun on my paper. However, I could barely hold the pen. I could not write a word, even though I kept all the beautiful words in my mind since yesterday’s twilight.

For an instant, my eyes were locked on the scene in front of me. It seemed nothing special was happening, but I was barely breathing: the sky was clear and the sun was shimmering. People in masks were walking here and there to get their daily groceries or just enjoying the fresh air. But something was not usual about that day. “Somewhere, something is wrong” sprang up in my mind.

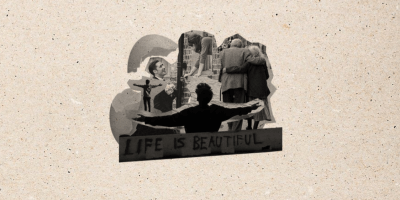

On the morning of Sept. 27, 2020, the hearts of Armenians were broken as we lost beautiful young lives and the land we fought for centuries to keep. The loss of them created a deep gap in our world, capturing our collective spirit and requiring us to walk a road of sorrow and grief. As a 15-year-old teenager who barely overcame the consequences of COVID-19, I was dead inside. I could not even cry over the people I lost in that war. I lost friends, a boy from my neighborhood who should have been accepted at one of the best universities in the world and created new beneficial things for humanity. But most importantly, I lost myself. Just in a moment, I could only think of leaving Armenia, leaving my kitchen window, which was the safest place in the whole world. The fear of losing the last piece of light in me covered my heart so hard that I barely breathed.

“Somewhere, something is wrong.” After three years of mourning the death of the happiness that left my heart, this was the only quote I could repeat myself so far. Whenever I go down the road in my town to the gloomy memorial of victims of the Artsakh war, a brief desire crosses my body to have my name engraved next to theirs. However, it disappears quickly, much like a strand of smoke swept away by the wind. However, I soon find peace in the simplicity of everyday life as I head to university, where I embrace the casual or academic talks with my friends, romanticizing the same war only as a distant scene from a movie rather than a harsh reality that once invaded our lives changing it forever.

Ararat’s majestic silhouette shone against the horizon on Sept. 27, 2023. Even though its majesty was covered with snow, in my eyes, Ararat didn’t seem peaceful that day. It’s already been eight days since, after the one-year blockade, Artskah was invaded again. “Somewhere, something is wrong,” crossed my mind for the second time today. While burying our sorrow in a dark coffee, my friends and I did not even talk about the recent news all of us were reading in the morning. It became a common thing for us: we did not fear loss or death.

However, instantly, tears started covering my face when the thought of imagining my family leaving Armenia haunted my mind. I was overwhelmed by the idea of leaving Armenia, saying goodbye to my friends, Yerevan, the view of Ararat, the crowded Baghramyan street and the life I had created. Being the child of immigrants, the anxiety of carrying on their heritage of loss and relocation runs through my veins like a cold reminder of the past. It has been three years that the only thing I wish for is to be an ordinary girl instead of being the embodiment of the cursed DNA of my ancestors who inherited the weight of a sorrowful legacy, bearing my grandfather’s sacrifice to defend his hometown and the resilience of my ancestors who barely survived the Genocide. But blood doesn’t become water. All of these are a part of my identity, part of who I am and who I will become.

Tears streamed down my face unchecked and my friends did not even ask why I was crying. Among them, my friend, who witnessed the war firsthand, who saw people falling halfway between life and death, broke the heavy silence, “None of us wants to leave the country, especially not me, knowing that I’ve defended it with my blood, witnessing the brutal reality of lives lost.” In his voice, I finally caught the last piece of hope I had been searching for a while. After a moment of silence, I affirmed, “Leaving is never an option, even if one sincerely wants to. But, apart from my Armenian identity, the idea of going somewhere else for a better future comes to mind. But how can I leave behind these mornings, the sight of Ararat, and the hellos of the old painter from my yard? How could I ever feel peaceful laying my head down somewhere else? Our connection to each piece of our country and each other appears unbreakable. Yet, I don’t know if it is our history, blood, or memories, but something strong doesn’t let us leave Armenia, the land of endurance.”

My friend smiled. Was it for the sun that penetrated his eyes or did he already unravel the mystery of the magical connection I was searching for? Was it the saddest smile of reconcilement with the idea of never returning to the highlands of Artsakh?

We will never know, but in that smile, as we gazed deeper into each other’s souls, amazed by the beauty of Ararat, we held onto the hope of cherishing our time together in our favorite place—blessed with the opportunity to enjoy a coffee with Ararat.

Our world appeared to stop for an instant, while time seemed to go on forever. Even though it was painful to leave Ararat behind, responsibility called us back to our studies. In the face of complex realities, we held fast to the hope that we would remain true to ourselves, working to strengthen our country and preserve our friendship that gave a sense of a second home and to be able to return to our safest places, as I can return to my kitchen window.