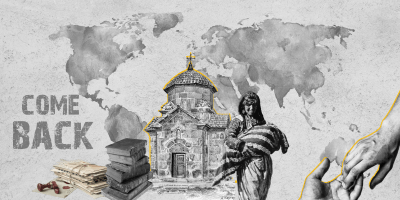

Nature demands that animals and humans find shelters to survive, but only humans try to transform that shelter into a home. Some people spend their lives in search of that home. Out of nature’s demands is the human construct of nationality that has both aided and hindered the feeling of home. Especially for Armenians, it has been a dilemma to find a place to belong to because of the strong attachment to their nationality, which is considered an essential part of their identity.

The estimated number of Armenians in the diaspora is seven million, which is more than double the number of Armenia’s current population which is close to three million. In these last few years, the number of Armenian repatriates has been increasing exponentially, but the number of those who feel at home remains questionable.

Meghrie Yaacoubian, an EC freshman, who moved from Lebanon to Armenia four years ago, explains that her nationalities have influenced her cultural identity and shaped how she views the world. “Having two nationalities makes me who I am, so I genuinely appreciate having them,” she says, “I am delighted to be affiliated with two countries rich in history and culture as someone interested in both.”

Unlike Meghrie, Armen Godjamanian, an EC junior and a repatriate from the United States, contradicts the idea of nationality and its correlation to one’s identity. “I always had a vague understanding of what nationality truly meant because you have a lot of people who are very attached to the country they live in and act upon it in different ways,” he continues, “I never knew how to act upon it.” He prefers leaving his nationality out of the queue of labels of his identity.

For some, even identifying as an Armenian and living in Armenia has not catalyzed the feeling of home. “I’ve been told I do not look like authentic Armenian and that I do not speak Armenian the way they do [Western],” Meghrie says, “I have realized that the local Armenians do not consider me as one of them, and they have treated me as an outsider, which is why I never felt like I belonged here.”

For Armen, it comes easier; even though he does not attach himself to his nationality, he feels at home in Armenia, “maybe sometimes too homey.” He considers himself lucky and privileged that he has not faced discrimination but, unfortunately, has seen other people from the diaspora become victims of discrimination. Having dual nationalities can be a beautiful thing. However, it creates a conundrum in feeling a sense of belonging to either nationality without facing prejudice from the internal community of the particular nation.

It is hard to separate nationality from identity since social construct demands us not to do so. Yet, it need not always be a hassle. Even having a deep affinity to one’s nationality with identity, one might feel at home somewhere apart from their nation.

Samantha Adalia, an EC senior, a Filipino who moved to Armenia six years ago and lived in Nepal for six years, describes nationality as something to be proud of. “I grew up being taught that it [nationality] is part of my identity,” she says.

Even with her strong attachment to her nationality, Samantha explains, “I feel more at home here (Armenia). However, because I have lived outside of my country for half of my life now, I think I’m more at home with the life of moving or globe-trotting.”

Sometimes, the quest to find a home can be completed in the least expected places. It does not have to be in a specific nation or city; it is wherever you create it, whether in a small nook, in people, or yourself. It is a feeling of belonging.

Like Meghrie, who found her home when she started attending AUA, “since the people here made me feel welcome for once.” Home is not defined by nationality, home is what you make it.